Views on insomnia and “trouble sleeping” have undoubtedly changed throughout the past few decades. As it became more culturally acceptable to talk about insomnia, treatments began being requested. Three World Sleep Society sleep experts have watched the field grow, expand and change from the 90s to today.

From “Z Drugs” to CBT-I

For 44 years, Clete A. Kushida, MD, PhD has been working in the field of sleep medicine and research. Currently acting as Associate Chair, Division Chief and Medical Director of Stanford Sleep Medicine, he began working in the realm of insomnia in 1991.

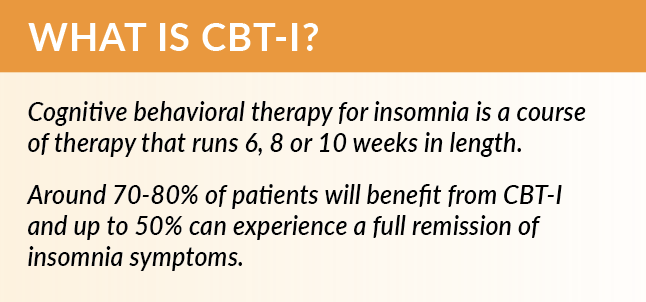

“Starting in July of 1991, I was a neurology resident at the University of California San Diego,” Dr. Kushida recalls. “I was fortunate in being able to evaluate sleep medicine patients under the supervision of Dr. Sonia Ancoli-Israel. At that time, many of the patients I saw with Dr. Ancoli-Israel were managed for their insomnia with antidepressants and benzodiazepines, including triazolam (Halcion).” In 1992, the FDA approved Zolpidem (Ambien) and it was the first of the “z drugs” (zolpidem, zopiclone, zaleplon) that rapidly became the first-line pharmacologic treatment for short-term insomnia. “Since that time,” Dr. Kushida explains, “there have been other pharmacologic treatments for short-term insomnia, including ramelteon and suvorexant. However, the most important treatment for insomnia that has grown during the last two decades is cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I), which has helped countless individuals with chronic insomnia.”

In the last ten years, there has been a virtual explosion in the need for CBT-I providers. At Stanford, Dr. Kushida has watched the increase to eight clinical psychologists, four behavioral sleep medicine fellows, and a nurse practitioner in two behavioral sleep medicine programs/clinics. Dr. Kushida states, “Even with this number of providers specializing in CBT-I, we have high demand for these services and are in the process of hiring additional providers. Given the prevalence of insomnia and these troubled times, I expect that the need for behavioral sleep medicine programs will continue to increase worldwide.”

Dr. Kushida sees the major inventions or advances that changed how we diagnose/treat insomnia as:

- Online and mobile CBT-I, particularly for those in geographical areas where a CBT-I provider is not necessarily accessible.

- The growth of consumer wearable devices as it helps to heighten awareness of sleep problems, including insomnia, in users, prompting them to seek help from sleep specialists.

- The use of actigraphy within sleep clinics to pinpoint sleep problems that may be circadian rhythm disorders, insomnia, or a combination of both.

Increased stress levels and insomnia symptoms associated with the COVID-19 pandemic has undoubtedly resulted in new and worsening cases of insomnia. Dr. Kushida remarks that the next few years will be interesting since wearable and home-based measures of sleep will show on a large-scale what impact the pandemic has had on the world’s population and will most likely result in even better treatments for insomnia.

Measuring Insomnia

Yuichi Inoue, MD, PhD began his career as a sleep researcher 35 years ago in hypersomnia and sleep apnea but came to work in insomnia, parasomnia and movement disorders around 2000. Currently Dr. Inoue is a Professor in the Department of Somnology at Tokyo Medical University.

According to Dr. Inoue, when he began his career, society paid minimal attention to the field of sleep medicine. Dr. Inoue states, “The clinical significance of insomnia was not sufficiently acknowledged, and many researchers (mainly psychiatrists) gave as much attention to insomnia as a comorbidity of psychiatric disorders. From the late 90s, the results of many epidemiological studies have revealed the clinical significance of insomnia and the importance of appropriate treatment on the disorder. Many physicians also came to know the harmful effect of long-term use of benzodiazepines or Z-drugs at that time.”

Dr. Inoue believes that in the past, patients relied too much on pharmacotherapy, especially GABAergic drugs. However, the enlightenment of sleep hygiene education, implementation of CBT-I and development of newer hypnotics such as melatonin receptor agonists and orexin receptor antagonists have changed the patients’ cognition and the outcome of treatments.

From 2005 forward, Dr. Inoue has been working with clinical psychiatrists specialized in CBT-I and created a series of papers on the efficacy of the treatment. Dr. Inoue states, “I truly believe that CBT-I is absolutely essential for the improvement of insomnia.” Currently, Dr. Inoue and his colleagues are conducting CBT-I via telemedicine, but the reliable outcome has not been obtained, despite there being some positive feelings. “We are also now studying the utility of sleep trackers—a conventional device—for the severity evaluation of insomnia and hope that this kind of easier testing would become a useful tool for the diagnosis of the disorder.”

Dr. Inoue sees the next step being to accumulate studies on the difference in psychological and physiological characteristics, as well as treatment strategy between objective and subjective insomnia. “I believe this will help the improvement of insomnia medicine,” he concludes.

Recognition of Insomnia

Dr. Colin Espie PhD, DSc(Med) is a Professor of Sleep Medicine at University of Oxford, UK who saw his first patient with insomnia in 1980, not long after qualifying clinically. Dr. Espie recalls a primary care physician asking at that time, “Can you not do anything to help these people who can’t sleep?” Dr. Espie had not received any training on sleep or sleep disorders but became fascinated to find out. He has been working to answer that question throughout his entire career.

“In the 90s, I think insomnia was seen mostly as a symptom of something else—most commonly depression—so the focus of professionals was upon treating what was thought to be the primary disorder. This never made sense to me. After all, depression is a dysfunctional mental end state that is more likely a result than a cause.” Dr. Espie noticed ‘impressive epidemiological research’ from the late 80s and 90s which demonstrated that insomnia was a risk factor for the development of depression (and other mental disorders). Moreover, he saw many patients who said sleep was fundamental to how they were feeling. “Unfortunately,” Dr. Espie comments, “it has taken us a long time to recognize what was always true—that sleep is of primary importance in the regulation of our emotional health.”

The publication in 2013 of DSM-5 and the inclusion of insomnia disorder as a disorder in its own right was a landmark event, according to Dr. Espie. “The evidence had been there for quite some time that insomnia should be actively addressed whenever it presented,” Dr. Espie states. “Indeed, we were seeing strong evidence that it could be effectively treated, particularly using CBT, but the clear direction given by DSM-5 brought insomnia out from under the coat tails of a very traditional psychiatry view of the world.” Other landmarks to note in the field of insomnia are the NIH state-of-the-science statement on insomnia (2005), the publication of AASM practice parameters (2006) and further iterations of ICSD (2005, 2014). “These all played a part in gathering momentum to take the insomnia field forward,” says Dr. Espie. “I also remember in the 2000s, noticing at scientific meetings that the insomnia sessions were getting better attended, were being held in larger halls, and becoming much more prominent rather than appearing on the last day when folks were about to head for home.”

Dr. Espie would “love to say that the patient’s experience has changed dramatically,” and notes that it has for some patients and in some places, but does feel we still have a long way to go to treat insomnia based upon clinical guideline care. Many in the field remember that in the early 90s, the default action would have been to pick up the prescription pad and use hypnotic drugs. There is more reluctance to do that nowadays, and sleep hygiene is at least being discussed in most clinics. Unfortunately, there is little evidence that sleep hygiene is an adequate standalone treatment for chronic insomnia, and the majority of people are still prescribed medication. Dr. Espie explains, “All guidelines recommend CBT-I as a first-choice treatment for persistent insomnia in adults of any age, and although provision of CBT-I has increased, it still falls dramatically short of what would be required to meet population need.”

CBT-I has proven to be very adaptable to a wide range of delivery formats. Traditionally, clinicians would meet with patients on a one-on-one basis, but CBT-I is also effective when delivered in small groups, or in abbreviated format, and using technology such as telehealth and digital (web mobile) tools. “I have for a long time advocated for the adoption of a stepped care model of insomnia treatment delivery so that patients can be triaged to accessible help based on clinical need, coupled with personal preference,” Dr. Espie explains. “The therapies that comprise what I now call cognitive behavioral therapeutics (CBTx) to emphasize that CBT is a class of intervention, have proven extraordinarily adaptable to different means of presentation, whilst retaining noticeable clinical effectiveness.” Dr. Espie also notes that digital CBT (dCBT) has the potential to transform service provision because fully automated software is as scalable as drugs.

“I anticipate that within five years dCBT will replace sleeping pills and off-label prescribing as the most commonly used insomnia treatment,” Dr. Espie relays. “We are entering the era of ‘digital medicine’ as a direct alternative to pharmaceutical medicine, and this is the most likely way in which clinical guideline care for insomnia can be delivered nationally and internationally. I am hopeful also that novel CBTx and pharmacotherapy interventions will continue to be developed because around one-third of our patients do not respond to the treatments we have. There is no room for complacency.”