I was always fascinated by the conventional wisdom and personal experience that sleep helps fight infections. And isn’t it interesting that, on the other hand, not sleeping enough makes us more susceptible to get infected? There is something happening during sleep that makes the immune system stronger or more successful in the fight against viruses and other pathogens.

HOW SLEEP POSITIVELY IMPACTS IMMUNITY

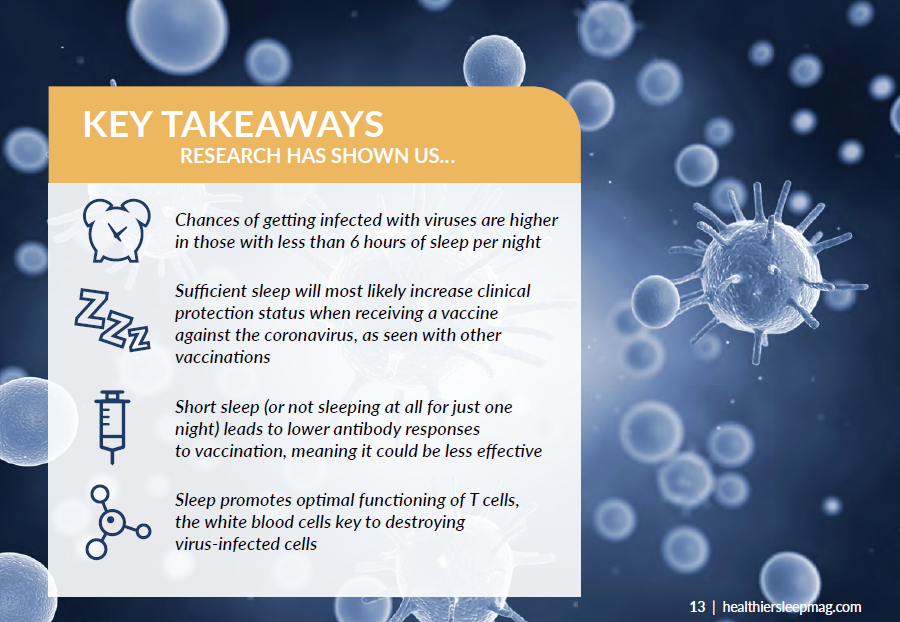

The many animal studies that have been done over the past decades have clearly shown that sleep helps an animal survive an infection. In humans, the chances of getting infected with respiratory viruses, for example, are much higher in those with short sleep (generally less than 6 hours per night) or those who suffer from insomnia. Short sleep or not sleeping at all for just one night also leads to lower antibody responses to vaccination, for example, against the flu.

In some people, the antibody response is so low that they are not sufficiently protected against the virus anymore. To keep in mind, both good sleep before and after a vaccination help to develop a strong antibody response against pathogens.

There are different ways sleep can support immunity. One way is that sleep protects against the development of low-grade inflammation. If inflammatory markers increase in the body, as has been seen with short or disturbed sleep, various immune cells are much less sufficient in fighting viruses and other pathogens.

There are also many hormones—such as cortisol, melatonin or epinephrine—that can suppress or promote inflammation. The secretion of these hormones can be circadian or sleep-dependent, so that is another way sleep can affect pathogen defense. There is also recent evidence that sleep promotes optimal functioning of T cells. T cells are a type of white blood cell that are key to the immune system. If the person is sleep deprived, T cells have difficulties attaching to virus-infected cells and consequently, cannot destroy them as they should.

STUDYING SLEEP & THE IMMUNE SYSTEM

Generally, researchers experimentally manipulate the amount of sleep, by completely sleep depriving animals or human participants or reducing the amount of sleep, most often to 4 hours of sleep per night over one or more nights. This can be done (and has been done) prior to and/or after exposure to a virus or vaccine to study how sleep-deprived cells respond to such a challenge. In addition to studying immune responses, we also look at the development of classical sickness symptoms—such as fatigue or body pain—when sleep deprived.

Another important topic is recovery. There are more and more data suggesting that recovery of biological processes from insufficient sleep can take longer. There are also now methodologies by which deep or slow wave sleep can be intensified through acoustic stimulation. Slow wave sleep is thought to be the sleep stage that is most critical for the immune supportive actions of sleep. This all aims to narrow in on the connection between sleep and immunity.

Because of COVID-19, 2021 will likely continue to be a year with high infection risk but also a year in which millions of people will get vaccinated. While there is not a lot of data yet specifically on sleep and COVID-19 infections, it is most likely that getting sufficient sleep around the time of infection can reduce the severity of the infection and promote a successful recovery.

And in the case of vaccination, sufficient sleep will most likely increase clinical protection status, as we have seen with other vaccinations. I think an important question is also the role of sleep in those individuals who do not recover from the infection. For those who continue to suffer from fatigue, body pain, headache and other sickness symptoms long after the virus is under control, I would be interested to see data on sleep in these long-haulers. Perhaps sleep interventions could potentially help recover from these symptoms more quickly.

TAKE ACTION

I hope people see that they can take control over their own immune health by changing their behavior; by making more time for sleep so the immune system can function at its best. For the average adult, this means 7 or more hours of undisturbed sleep per night, best with regular bed and wake times. I actually think that many people know that already, but don’t do it because behavioral changes are generally difficult to make and to maintain. Let’s choose to better our sleep to better our immunity.

……………………………………………….

Monika Haack, PhD is an Associate Professor of Neurology at Harvard Medical School Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center who has been working in the field of sleep medicine & research for 18 years.

One Response

I can only agree. It is right to remind people of the importance of sleep. The paragraph on acoustic stimulation of sleep by slow waves appealed to me. It would certainly be useful to write more about it. Well thank you.